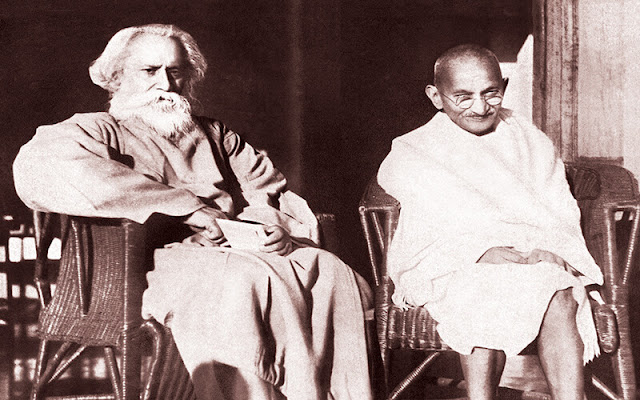

163rd birth anniversary of Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore

Tagore and Gandhi : The beauty of in-depth debates

When Mahatma Gandhi came and

opened up the path of freedom for India, he had no obvious medium of power in his

hand, no overwhelming authority of coercion. The influence which emanated from his

personality was ineffable, like music, like beauty. Its claim upon others was great

because of its revelation of a spontaneous self-giving. This is the reason why our

people have hardly ever laid emphasis upon his natural cleverness in manipulating

recalcitrant facts. They have rather dwelt upon the truth which shines through his

character in lucid simplicity.

Rabindranath Tagore

Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi maintained a unique relationship despite their differences on some key issues. Gandhi returned to India in 1915 and Gurudev welcomed his Phoenix party at Shantiniketan and gave Gandhi a free hand to undertake experiments in education at his ashram, and described it as key to swaraj. This reveals Gurudev’s acceptance of Gandhi’s ideas and ideals. It continued throughout their lives while expressing their difference on certain issues publicly. It was Dr.Pranjivan Mehta who hinted first about Gandhi’s evolution to the status of a Mahatma in a letter addressed to G. K. Gokhale in 1909. However, the credit goes to Rabindranath Tagore for giving the name Mahatma to M. K. Gandhi.

In a Webinar jointly organized by Sevagram Ashram Pratishthan Wardha, Maharashtra;Centre for

Gandhian Studies, Central University of Kerala and ProbhodhaTrust, Kochi in May 2021, Prof. John Moolakkattu, the Chief Editor of

Gandhi Marg, New Delhi while delivering the presidential address said Only a

person like Tagore can say: “Where the mind is without fear and the head

is held high; Where knowledge is free; Where the world has not been broken up

into fragments by narrow domestic walls; Where words come out from the depth of

truth” Both Tagore and Gandhi were ardent seekers of truth with a universal

vision. We need to look at their views to understand truth in a comprehensive

way though they understood truth differently. What is missing in India is lack

of such in-depth debates which is essential for preserving the rich democratic

traditions of our country.

The Poet and the Charkha

When

Sir Rabindranath’s criticism of charkha was published some time ago, several

friends asked me to reply to it. Being heavily engaged, I was unable then to

study it in full. But I had read enough of it to know its trend. I was in no

hurry to reply. Those who had read it were too much agitated or influenced to

be able to appreciate what I might have then written even if I had the time.

Now, therefore, is really the time for me to write on it and to ensure a

dispassionate view being taken of the Poet’s criticism or my reply, if such it

may be called.

The

criticism is a sharp rebuke to Acharya Ray for his impatience of the Poet’s and Acharya

Seal’s position regarding the charkha, and gentle rebuke to me for my exclusive

and excessive love of it. Let the public understand that the Poet does not deny

its great economic value. Let them know that he signed the appeal for the All India

Deshbandhu Memorial after he had written his criticism. He signed the appeal

after studying its contents carefully and, even as he signed it, he sent me the

message that he had written something on the charkha which might not quite

please me. I knew, therefore, what was coming. But it has not displeased me.

Why should mere disagreement with my views displease? If every disagreement

were to displease, since no two men agree exactly on all points, life would be

a bundle of unpleasant sensations and, therefore, a perfect nuisance. On the

contrary the frank criticism pleases me. For our friendship becomes all the

richer for our disagreements. Friends to be friends are not called upon to

agree even on most points, Only disagreements must have no sharpness, much less

bitterness, about them. And I gratefully admit that there is none about the

Poet’s criticism.

I

am obliged to make these prefatory remarks as dame rumour has whispered that

jealousy is the root of all that criticism. Such baseless suspicion betrays an

atmosphere of weakness and intolerance. A little reflection must remove all

ground for such a cruel charge. Of what should the Poet be jealous in me?

Jealousy presupposes the possibility of rivalry. Well, I have never succeeded

in writing a single rhyme in my life. There is nothing of the Poet about me. I

cannot aspire after his greatness. He is the undisputed master of it. The world

today does not possess his equal as a poet. My ‘mahatmaship’ has no relation to

the Poet’s undisputed position. It is time to realize that our fields are

absolutely different and at no point overlapping. The Poet lives in a

magnificent world of his own creation—his world of ideas. I am a slave of

somebody else’s creation—the spinning-wheel. The Poet makes his gopis dance to

the tune of his flute. I wander after my beloved Sita, the charkha, and seek to

deliver her from the ten-headed monster from Japan, Manchester, Paris, etc. The

Poet is an inventor— he creates, destroys and recreates. I am an explorer and

having discovered a thing, I must cling to it. The Poet presents the world with

new and attractive things from day to day. I can merely show the hidden

possibilities of old and even worn-out things. The world easily finds an

honourable place for the magician who produces new and dazzling things. I have

to struggle laboriously to find a corner for my worn-out things. Thus there is

no competition between us. But I may say in all humility that we complement

each other’s activity.

The

fact is that the Poet’s criticism is a poetic licence and he who takes it

literally is in danger of finding himself in an awkward corner. An ancient poet

has said that Solomon arrayed in all his glory was not like one of the lilies

of the field. He clearly referred to the natural beauty and innocence of the

lily contrasted with the artificiality of Solomon’s glory and his sinfulness in

spite of his many good deeds. Or take the poetical licence in: ‘It is easier

for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter

the Kingdom of Heaven.’ We know that no camel has ever passed through the eye of

a needle and we know too that rich men like Janaka have entered the Kingdom of

Heaven. Or take the beautiful simile of human teeth being likened to the

pomegranate seed. Foolish women who have taken the poetical exaggeration

literally have been found to disfigure, and even harm, their teeth. Painters

and poets are obliged to exaggerate the proportions of their figures in order

to give a true perspective. Those therefore who take the Poet’s denunciation of

the charkha literally will be doing an injustice to the Poet and an injury to

themselves.

The

Poet does not, he is not expected, he has no need, to read Young India. All he

knows about the movement is what he has picked up from table talk. He has,

therefore, denounced what he has imagined to be the excesses of the charkha

cult.

He

thinks, for instance, that I want everybody to spin the whole of his or her

time to the exclusion of all other activity, that is to say, that I want the

poet to forsake his muse, the farmer his plough, the lawyer his brief and the

doctor his lancet. So far is this from truth that I have asked no one to

abandon his calling but, on the contrary, to adorn it by giving every day only

thirty minutes to spinning as sacrifice for the whole nation. I have, indeed,

asked the famishing man or woman who is idle for want of any work whatsoever to

spin for a living and the half-starved farmer to spin during his leisure hours

to supplement his slender resources. If the Poet span half an hour daily his

poetry would gain in richness. For it would then represent the poor man’s wants

and woes in a more forcible manner than now.

The

Poet thinks that the charkha is calculated to bring about a death-like sameness

in the nation and, thus imagining, he would shun it if he could. The truth is

that the charkha is intended to realize the essential and living oneness of

interest among India’s myriads. Behind the magnificent and kaleidoscopic

variety, one discovers in nature a unity of purpose, design and form which is

equally unmistakable. No two men are absolutely alike, not even twins, and yet

there is much that is indispensably common to all mankind. And behind the

commonness of form there is the same life pervading all. The idea of sameness

or oneness was carried by Shankara to its utmost logical and natural limit and

he exclaimed that there was only one truth, one God—Brahman—and all form, nam,

rupa was illusion or illusory, evanescent. We need not debate whether what we

see isunreal; and whether the real behind the unreality is what we do not see.

Let both be equally real, if you will. All I say is that there is a sameness,

identity or oneness behind the multiplicity and variety. And so do I hold that

behind a variety of occupations there is an indispensable sameness also of

occupation. Is not agriculture common to the vast majority of mankind? Even so,

was spinning common not long ago to a vast majority of mankind? Just as both

prince and peasant must eat and clothe themselves so must both labour for

supplying their primary wants. The prince may do so if only by way of symbol

and sacrifice, but that much is indispensable for him if he will be true to

himself and his people. Europe may not realize this vital necessity at the

present moment, because it has made of exploitation of non-European races a

religion. But it is a false religion bound to perish in the near future. The

non-European races will not for ever allow themselves to be exploited. I have

endeavoured to show a way out that is peaceful, humane and, therefore, noble.

It may be rejected if it is, the alternative is a tug of war, in which each

will try to pull down the other. Then, when non-Europeans will seek to exploit

the Europeans, the truth of the charkha will have to be realized. Just as, if

we are to live, we must breathe not air imported from England nor eat food so

imported, so may we not import cloth made in England. I do not hesitate to

carry the doctrine to its logical limit and say that Bengal dare not import her

cloth even from Bombay or from Banga Lakshmi. If Bengal will live her natural

and free life without exploiting the rest of India or the world outside, she

must manufacture her cloth in her own villages as she grows her corn there.

Machinery has its place; it has come to stay. But it must not be allowed to

displace the necessary human labour. An improved plough is a good thing. But

if, by some chance, one man could plough up by some mechanical invention of his

the whole of the land of India and control all the agricultural produce and if

the millions had no other occupation, they would starve, and being idle, they

would become dunces, as many have already become. There is hourly danger of

many more being reduced to that unenviable state. I would welcome every

improvement in the cottage machine, but I know that it is criminal to displace

the hand labour by the introduction of power driven spindles unless one is, at

the same time, ready to give millions of farmers some other occupation in their

homes.

The

Irish analogy does not take us very far. It is perfect in so far as it enables

us to realize the necessity of economic co-operation. But Indian circumstances

being different, the method of working out cooperation is necessarily

different. For Indian distress every effort at co-operation has to centre round

the charkha if it is to apply to the majority of the inhabitants of this vast

peninsula 1,900 miles long and 1,500 broad. Sir Gangaram may give us a model

farm which can be no model for the penniless Indian farmer, who has hardly two

to three acres of land which every day runs the risk of being still further cut

up.

Round

the charkha, that is amidst the people who have shed their idleness and who

have understood the value of co-operation, a national servant would build up a

programme of anti-malaria campaign, improved sanitation, settlement of village

disputes, conservation and breeding of cattle and hundreds of other beneficial

activities. Wherever charkha work is fairly established, all such ameliorative

activity is going on according to the capacity of the villagers and the workers

concerned.

It

is not my purpose to traverse all the Poet’s arguments in detail. Where the

differences between us are not fundamental—and these I have endeavoured to

state—there is nothing in the Poet’s argument which I cannot endorse and still

maintain my position regarding the charkha. The many things about the charkha

which he has ridiculed I have never said. The merits I have claimed for the

charkha remain undamaged by the Poet’s battery.

One

thing, and one thing only, has hurt me, the Poet’s belief, again picked up from

table talk, that I look upon Ram Mohan Roy as a ‘pigmy’. Well, I have never

anywhere described that great reformer as a pigmy much less regarded him as

such. He is to me as much a giant as he is to the Poet. I do not remember any

occasion save one when I had to use Ram Mohan Roy’s name. That was in

connection with Western education. This was on the Cuttack sands now four years

ago. What I do remember having said was that it was possible to attain highest

culture without Western education. And when someone mentioned Ram Mohan Roy, I

remember having said that he was a pigmy compared to the unknown authors, say,

of the Upanishads. This is altogether different from looking upon Ram Mohan Roy

as a pigmy. I do not think meanly of Tennyson if I say that he was a pigmy

before Milton or Shakespeare. I claim that I enhance the greatness of both. If

I adore the Poet, as he knows I do in spite of differences between us, I am not

likely to disparage the greatness of the man who made the great reform movement

of Bengal possible and of which the Poet is one of the finest of fruits.

Young

India

5-11-1925

Comments

Post a Comment